By JONATHAN LEMIRE and ZEKE MILLER

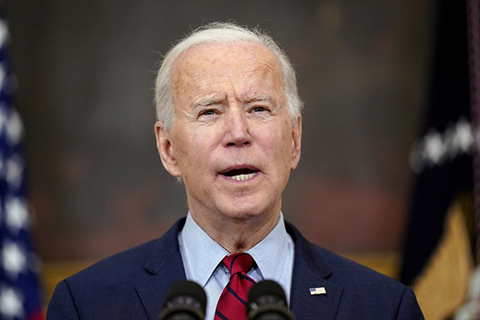

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Joe Biden held off on holding his first news conference so he could use it to celebrate passage of a defining legislative achievement, his giant COVID-19 relief package. But he’s sure to be pressed at Thursday’s question-and-answer session about all sorts of other challenges that have cropped up along the way.

A pair of mass shootings, rising international tensions, early signs of intraparty divisions and increasing numbers of migrants crossing the southern border are all confronting a West Wing known for its message discipline.

Biden is the first chief executive in four decades to reach this point in his term without holding a formal question-and-answer session. He’ll meet with reporters for the nationally televised afternoon event in the East Room of the White House.

“It’s an opportunity for him to speak to the American people, obviously directly through the coverage, directly through all of you,” White House press secretary Jen Psaki told reporters aboard Air Force One on Tuesday. “And so I think he’s thinking about what he wants to say, what he wants to convey, where he can provide updates, and, you know, looking forward to the opportunity to engage with a free press.”

While Biden has been on pace with his predecessors in taking questions from the press in other formats, he tends to field just one or two informal inquiries at a time, usually in a hurried setting at the end of an event or in front of a whirring helicopter.

Pressure had mounted on Biden to hold a formal session, which allows reporters to have an extended back-and-forth with the president on the issues of the day. Biden’s conservative critics have pointed to the delay to suggest that Biden was being shielded by his staff.

West Wing aides have dismissed the questions about a news conference as a Washington obsession, pointing to Biden’s high approval ratings while suggesting that the general public is not concerned about the event. The president himself, when asked Wednesday if he were ready for the press conference, joked, “What press conference?”

Behind the scenes, though, aides have taken the event seriously enough to hold a mock session with the president earlier this week. And there is some concern that Biden, a self-proclaimed “gaffe machine,” could go off message and generate a series of unflattering news cycles.

“The press conference serves an important purpose: It presents the press an extended opportunity to hold a leader accountable for decisions,” said Kathleen Hall Jamieson, presidential scholar and professor of communication at the University of Pennsylvania. “A question I ask: What is the public going to learn in this venue that it couldn’t learn elsewhere? And why does it matter? The answer: The president speaks for the nation.”

Biden will stand behind a lectern emblazoned with the presidential seal and point to a surge in vaccine distribution, encouraging signs in the economy and the benefits Americans will receive from the sweeping stimulus package. But plenty of challenges abound.

His appearance will come just a day after he appointed Vice President Kamala Harris to lead the government’s response to the situation at the U.S.-Mexico border, where the administration faces a growing humanitarian and political challenge that threatens to overshadow Biden’s legislative agenda.

In less than a week, two mass shootings have rattled the nation and pressure has mounted on the White House to back tougher gun measures. The White House has struggled to blunt a nationwide effort by Republican legislatures to tighten election laws. A pair of Democratic senators briefly threatened to hold up the confirmation of Biden appointees due to a lack of Asian-American representation in the Cabinet. And both North Korea and Russia have unleashed provocative actions to test a new commander in chief.

In a sharp contrast with the previous administration, the Biden White House has exerted extreme message discipline, empowering staff to speak but doing so with caution. The new White House team has carefully managed the president’s appearances, which serves Biden’s purposes but denies the media opportunities to directly press him on major policy issues and to engage in the kind of back-and-forth that can draw out information and thoughts that go beyond curated talking points.

Having overcome a childhood stutter and famously long-winded, Biden has long enjoyed interplay with reporters and has defied aides’ requests to ignore questions from the press. He has been prone to gaffes throughout his long political career and, as president, has occasionally struggled with off-the-cuff remarks.

Those are the types of distractions his aides have tried to avoid, and, in a pandemic silver lining, were largely able to dodge during the campaign because the virus kept Biden home for months and limited the potential for public mistakes.

Firmly pledging his belief in freedom of the press, Biden has rebuked his predecessor’s incendiary rhetoric toward the media, including Donald Trump’s references to reporters as “the enemy of the people.” Biden restored the daily press briefing, which had gone extinct under Trump, opening a window into the workings of the White House. And he sat for a national interview with ABC News last week.

Biden has also delivered a series of well-received speeches, including his inaugural address, and has shown that he can effectively communicate beyond news conferences, according to Frank Sesno, former head of George Washington University’s school of media.

“His strongest communication is not extemporaneous. He can ramble or stumble into a famous Biden gaffe,” said Sesno in a recent interview. “But to this point, he and his team have been very disciplined with the message of the day and in hitting the words of the day.”