By WILL WEISSERT

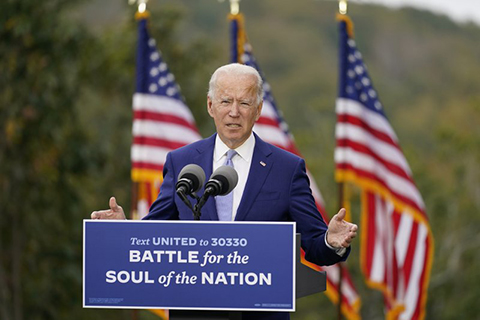

WASHINGTON (AP) — Back when the election was tightening and just a week away, Joe Biden went big.

He flew to Warm Springs, the Georgia town whose thermal waters once brought Franklin Delano Roosevelt comfort from polio, and pledged a restitching of America’s economic and policy fabric unseen since FDR’s New Deal.

Evoking some of the nation’s loftiest reforms helped Biden unseat President Donald Trump but left him with towering promises to keep. And he’ll be trying to deliver against the backdrop of searing national division and a pandemic that has killed nearly 400,000 Americans and upended the economy.

Such change would be hard to imagine under any circumstances, much less now.

He’s setting out with Democrats clinging to razor-thin House and Senate control and after having won an election in which 74 million people voted for his opponent. And even if his administration accomplishes most of its top goals in legislation or executive action, those actions are subject to being struck down by a Supreme Court now controlled by a 6-3 conservative majority.

Even so, the effort is soon underway. Washington is bracing for dozens of consequential executive actions starting Wednesday and stretched over the first 10 days of Biden’s administration, as well as legislation that will begin working its way through Congress on pandemic relief, immigration and much more.

Has Biden promised more than he can deliver? Not in his estimation. He suggests he can accomplish even more than he promised. He says he and his team will “do our best to beat all the expectations you have for the country and expectations we have for it.”

Some Democrats say Biden is right to set great expectations while realizing he’ll have to compromise, rather than starting with smaller goals and having to scale them back further.

“You can’t say to a nation that is hungry, uncertain, in some places afraid, whose economy has stalled out … that you had to slim down the request of their government because you have a narrow governing margin,” said former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick, Biden’s onetime Democratic presidential primary rival.

New presidents generally enjoy a honeymoon period that helps them in Congress, and Biden’s prospects for getting one were improved by Democratic victories this month in two Georgia special Senate elections. He may have been helped, too, by a public backlash against the deadly, armed insurrection at the U.S. Capitol by Trump supporters.

Biden’s advisers have acknowledged they’ll have bitter fights ahead. One approach they have in mind is a familiar one in Washington — consolidating some big ideas into what is known as omnibus legislation, so that lawmakers who want popular measures passed have to swallow more controversial measures as well.

Another approach is to pursue goals through executive orders. Doing so skirts Congress altogether but leaves the measures more easily challenged in court. Trump made hefty use of executive orders for some of his most contentious actions, on border enforcement, the environment and more, but federal courts often got in the way.

Biden’s top priority is congressional approval of a $1.9 trillion coronavirus plan to administer 100 million vaccines by his 100th day in office while also providing $1,400 direct payments to Americans to stimulate the virus-hammered economy. That’s no slam dunk, even though everyone likes to get money from the government.

Any such payment is likely to be paired with measures many in Congress oppose, perhaps his proposed mandate for a $15 national minimum wage, for example. And Biden’s relief package will have to clear a Senate consumed with approving his top Cabinet choices and with conducting Trump’s potential impeachment trial.

Nevertheless, the deluge is coming.

On Day One alone, Biden has promised to extend the pause on federal student loan payments, move to have the U.S. rejoin the World Health Organization and Paris climate accord and ask Americans to commit to 100 days of mask-wearing. He plans to use executive actions to overturn the Trump administration’s ban on immigrants from several majority-Muslim countries and wipe out corporate tax cuts where possible, while doubling the levies U.S. firms pay on foreign profits.

That same day, Biden has pledged to create task forces on homelessness and reuniting immigrant parents with children separated at the U.S.-Mexico border. He’ll plan to send bills to Congress seeking to mandate stricter background checks for gun buyers, scrap firearm manufacturers’ liability protections and provide an eight-year path to citizenship for an estimated 11 million people living in the U.S. without legal status.

The new president further wants to relax limits immediately on federal workers unionizing, reverse Trump’s rollback of about 100 public health and environmental rules that the Obama administration instituted and create rules to limit corporate influence on his administration and ensure the Justice Department’s independence.

He also pledged to have 100 vaccination centers supported by federal emergency management personnel up and running during his first month in the White House.

Biden says he’ll use the Defense Production Act to increase vaccine supplies and ensure the pandemic is under enough control after his first 100 days in office for most public schools to reopen nationwide. He’s also pledged to have created a police oversight commission to combat institutional racism by then.

Among other major initiatives to be tackled quickly: rejoining the U.S.-Iran nuclear deal, a $2 trillion climate package to get the U.S. to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, a plan to spend $700 billion boosting manufacturing and research and development and building on the Obama administration’s health care law to include a “public option.”

Perhaps obscured in that parade of promises, though, is the fact that some of the 80 million-plus voters who backed Biden may have done so to oppose Trump, not because they’re thrilled with an ambitious Democratic agenda. The president-elect’s victory may not have been a mandate to pull a country that emerged from the last election essentially centrist so far to the left.

Republican strategist Matt Mackowiak predicted early Republican support for Biden’s coronavirus relief and economic stimulus spending plans, but said that may evaporate quickly if “they issue a bunch of first-day, left-wing executive orders.”

“You can’t be bipartisan with one hand and left-wing with the other,” Mackowiak said, “and hope that Republicans don’t notice.”

Biden had a front-row seat as vice president in 2009, when Barack Obama took office, with crowds jamming the National Mall, and promised to transcend partisan politics. His administration used larger congressional majorities to oversee slow economic growth after the 2008 financial crisis, and it passed the health law Biden now seeks to expand.

But Obama failed to get major legislation passed on climate change, ethics or immigration. He failed, too, to close the U.S. detention camp at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, which remains open to this day.

Falling short on promises then hasn’t made Biden more chastened today. He acknowledges that doing even a small portion of what he wants will require running up huge deficits, but he argues the U.S. has an “economic imperative” and “moral obligation” to do so.

Kelly Dietrich, founder of the National Democratic Training Committee and former party fundraiser, said the divisions fomented by Trump could give Biden a unique opportunity to push ahead immediately and ignore conservative critics who “are going to complain and cry and make stuff up” and argue that socialists are “coming to kick your puppy.”

Biden and his team would do well to brush off anyone who doesn’t think he can aim high, he said.

“They should not be distracted by people who think it’s disappointing or it can’t happen,” Dietrich said. “Overwhelm people with action. No administration, after it’s over, says, ’We accomplished too much in the first hundred days.’”