By LAUREN WEBER, LAURA UNGAR, MICHELLE R. SMITH, HANNAH RECHT and ANNA MARIA BARRY-JESTER

AP – The U.S. public health system has been starved for decades and lacks the resources necessary to confront the worst health crisis in a century.

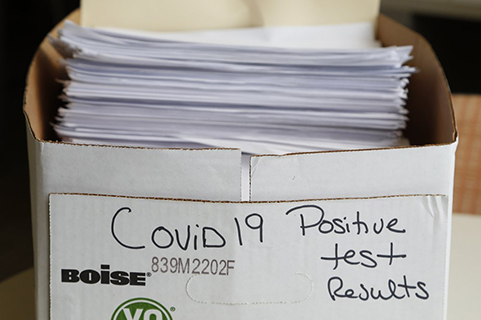

Marshaled against a pandemic that has sickened at least 2.6 million in the U.S., killed more than 126,000 people and cost tens of millions of jobs and $3 trillion in federal rescue money, state and local government health workers are sometimes paid so little, they qualify for public aid. They track the coronavirus on records shared via fax. Working seven-day weeks for months, they fear pay freezes, public backlash and even losing their jobs.

Since 2010, spending for state public health departments has dropped by 16% per capita and spending for local health departments has fallen by 18%, according to a KHN and Associated Press analysis. At least 38,000 state and local public health jobs have disappeared since the 2008 recession, leaving a skeletal workforce in some places.

KHN, also known as Kaiser Health News, and AP interviewed more than 150 public health workers, policymakers and experts, analyzed spending records from hundreds of state and local health departments, and surveyed statehouses. On every level, the investigation found, the system is underfunded and under threat.

Over time, state and local health departments received so little support that they found themselves without direction, ignored, even vilified.

With the economic downturn caused by the pandemic, states, cities and counties have begun laying off and furloughing staff, even as states reopen and cases surge.

“We don’t say to the fire department, ‘Oh, I’m sorry. There were no fires last year, so we’re going to take 30% of your budget away.’ That would be crazy, right?” said Dr. Gianfranco Pezzino, the health officer in Shawnee County, Kansas. “But we do that with public health, day in and day out.”

Ohio’s Toledo-Lucas County Health Department spent just $40 per person in 2017. When the coronavirus struck, it was so short-staffed that environmental health supervisor Jennifer Gottschalk’s duties included overseeing campground and pool inspections, rodent control and supervising outbreak preparedness.

When Gottschalk, 42, and five colleagues fell ill with COVID-19, she found herself fielding work calls from her hospital bed. “You have to do what you have to do to get the job done,” she said.

Nearly two-thirds of Americans live in counties that spend more than twice as much on policing as nonhospital health care, which includes public health.

The undervaluing of public health belies its multidimensional role. Distinct from the medical care system geared toward individuals, the public health system focuses on the health of communities at large. Agencies are legally bound to provide a broad range of essential services.

“Public health loves to say: When we do our job, nothing happens. But that’s not really a great badge,” said Scott Becker, chief executive officer of the Association of Public Health Laboratories. “We test 97% of America’s babies for metabolic or other disorders. We do the water testing. You like to swim in the lake and you don’t like poop in there? Think of us.”

But the public doesn’t see the disasters they thwart. And it’s easy to neglect the invisible.

___

A HISTORY OF DEPRIVATION

The federal government’s occasional promises to support local public health efforts were ephemeral.

For example, the Affordable Care Act established the Prevention and Public Health Fund, which was supposed to reach $2 billion annually by 2015. But the Obama administration and Congress raided it for other priorities, and now the Trump administration is pushing to repeal the ACA, which would eliminate it.

If it had remained untouched, an additional $12.4 billion would eventually have flowed to local and state health departments, strengthening them for today’s pandemic.

Local and state leaders also failed to prioritize public health. In North Carolina, for example, Wake County’s public health workforce dropped from 882 in 2007 to 614 a decade later, even as the population grew by 30%.

Years of financial cuts left this predominantly female workforce stretched thin. More than a fifth of public health workers in local or regional departments outside big cities earned $35,000 or less a year in 2017, according to research by the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials and the de Beaumont Foundation. Nearly half of public health workers planned to retire or leave their organizations in the next five years, with poor pay topping the list of reasons.

Two years ago, Julia Crittendon, now 46, took a job with Kentucky’s state health department. She spent her days gathering information about people’s sexual partners to fight the spread of HIV and syphilis. She earned so little she qualified for Medicaid, the federal-state insurance program for America’s poorest. Seeing no opportunity to advance, she left.

Since the pandemic began, state and local public health leaders have been leaving in droves. At least 34 announced their resignation, retired or got fired in 17 states since April, a KHN/AP review found.

___

FROM BAD TO WORSE

Scott Lockard, public health director for the Kentucky River District Health Department in Appalachia, is fighting the virus with 3G cell service, paper records and one-third of the employees the department had 20 years ago.

In rural Missouri, Melanie Hutton, administrator for the Cooper County Public Health Center, said her state gave $18,000 to the local ambulance department to fight COVID and provided masks to the fire and police departments.

“For us, not a nickel, not a face mask,” she said. “We got (5) gallons of homemade hand sanitizer made by the prisoners.

Since the pandemic began, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials said, the federal government has allocated more than $13 billion for state and local health department activities including contact tracing, infection control and technology upgrades.

But at least 14 states have already cut health department budgets or positions or were actively considering such cuts in June, according to a KHN/AP review.

Reductions threaten to limit crucial programs such as immunization clinics, mosquito control, diabetes and senior nutrition programs. Such cuts can make already-vulnerable communities even more vulnerable, said E. Oscar Alleyne, chief of programs and services at the National Association of County and City Health Officials.

The people who spend their lives working in public health worry they are seeing a familiar pattern — officials neglect this infrastructure and then, when a crisis emerges, they respond with a quick cash infusion. While that temporary money is necessary to fight the pandemic, public health experts say it won’t fix the eroded foundation entrusted with protecting the nation’s health as thousands continue to die.

___

Michelle R. Smith is a correspondent for the AP, and Lauren Weber, Hannah Recht, Laura Ungar and Anna Maria Barry-Jester are writers for KHN.

___

Contact AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org.

___

This story is a collaboration between The Associated Press and KHN (Kaiser Health News), which is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation) that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.